Is the CPCS delivering? Or is it too soon to tell?

In Services Development

Follow this topic

Bookmark

Record learning outcomes

The Community Pharmacy Consultation Service (CPCS), which sees the wider NHS refer patients to community pharmacy, was introduced as an advanced service in the five-year Community Pharmacy Contractual Framework (CPCF).

It formalises, to a degree, what happens already through informal consultations coming via GP practices, but it is also a potential way to generate new consultations in community pharmacy by redirecting patients from other parts of the NHS. It has been operating since October 2019 for referrals from NHS 111 and since November 2020 for referrals from GP practices.

Adding value but not income

Community pharmacy is a first port of call for many people. For some, it’s to pick up a prescription or buy an over-the-counter medicine. But when getting advice is the motivation, it becomes a consultation, not a visit.

When people travel to a community pharmacy, they show a revealed preference. That implies that they see value in going. When a GP practice refers to a community pharmacy, that also implies that the practice staff not only believe it’s appropriate, but also brings value in terms of what the GP practice can do with the appointment that is freed up. This creates an interesting challenge for those thinking about why a GP practice might or might not refer into the service – there are two boxes to be ticked, not one. The same goes for other parts of the NHS.

The CPCF noted that the potential volume of CPCS referrals wasn’t known at the time the contract was released in 2019, but that an estimated 20 million appointments in general practice didn’t require a GP.

PSNC’s 2021 Pharmacy Advice Audit ran from 25 January to 12 February.1 Close to 6,000 community pharmacies in England recorded all consultations on one day, or however long it took to reach 20 consultations. Based on this, PSNC estimates that there are over 1.1 million informal consultations in community pharmacies every week, each taking staff just over five minutes. That’s equivalent to 58 million informal consultations a year, or around 17 a day per community pharmacy. While those with a critical eye will point out that this was just one day in winter, during a global pandemic, and it was self-reported, which raises questions about whether it’s representative, it’s still clear that community pharmacy is delivering a lot of informal consultations. Those numbers are also pretty consistent with PSNC’s audit from 2020.2

It’s hard to put a pounds and pence figure on it, but it would seem like community pharmacy is delivering a lot of added value through informal consultations. Even more so when the same audit suggested that expert advice was given in 97 per cent of these consultations.

For the NHS too there is a benefit; half of those seeking advice said they would have otherwise attended a GP practice. And the reward for community pharmacy? Just over a half (54 per cent) of these informal consultations led to the sale of a medicine. And a sense of a job well done, of course, since money is not the sole motivator of community pharmacy teams.

We could debate the merit of whether the margin on an OTC sale is an appropriate reward. Many OTC medicines are relatively inexpensive, so these consultations in and of themselves are hardly lucrative, and the 46 per cent that did not result in a sale come at a cost to the pharmacy.

Are the incentives strong enough?

Paid at £14 per consultation, CPCS appears, on the face of it, to be a win-win-win. Patients could well get faster access to a healthcare professional while other parts of the NHS can focus their care on those who need it most and help manage demand. Community pharmacies get a stream of income. But, as with everything in the NHS, it’s never quite as simple as that.

On the demand side, for the wider NHS, there is the incentive that is the potential to ease pressure. But there is an upfront cost: new ways of working need training and infrastructure and these – even if they are free – still need an investment of time.

The argument may be that since CPCS has no ongoing financial cost (a GP practice can refer into it with no impact on its budget), the incentives are there. But in reality, it can be hard to invest the upfront time. Even one referral will take up practice staff time. And time is a precious resource in a GP practice.

It’s not just an investment challenge either. What if patients who are referred to community pharmacy simply bounce back into the practice? This will be the ‘right’ thing for some patients – community pharmacists can spot clinical issues that require GP or A&E consultations – but it may not be for others, who may bounce back for different reasons. Patients may still want the reassurance of seeing a GP, for example, even when they have been given appropriate clinical advice by the community pharmacist, or it may be that they feel the issue has not been resolved for them.

Teasing out the potential waste and its drivers is hard. GP practices may wonder if they are just adding more work without a payoff. Are they confident the local pharmacy can deliver the quality of consultation required so that no more care is needed? Or will they see the same patient at a later date?

Getting a GP practice to refer is only part of what will shape demand for CPCS. Patients aren’t obliged to accept a referral. They could still decide to access care from other parts of the NHS. For them, it’s about the balance of the cost (time as well as money to travel to access care) versus perceived benefit. Rightly or wrongly, a GP appointment or other NHS service may still be preferred. Doubling up needlessly on consultations, no matter the cause, would be wasteful.

CPCS is not, strictly speaking, new money for community pharmacies. It is a replacement for the NHS urgent medicines supply advanced service (NUMSAS) and the digital minor illness referral service (DMIRS), and is funded by recycling monies previously paid for MURs and in the consolidation into the Single Activity Fee. CPCS is voluntary for community pharmacists and not every pharmacy will be able to sign up; a consultation room is a requirement, for example. Some may question whether it’s worth it at all.

A missed opportunity

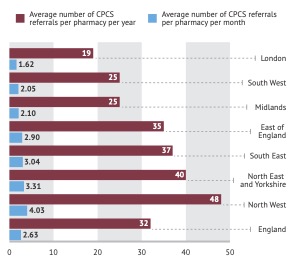

by NHS England region, per year and per month

By June 2020, CPCS referrals from NHS 111 and GPs had topped 332,000, according to NHS England and NHS Improvement.3 That’s a monthly rate – taking October 2019 as the start date – of close to 37,000 a month for England as a whole. In analysis of the 12 months to March 2021, PharmData put the total at just over 336,000, suggesting a bit of a drop off to an average monthly rate of just over 28,000.

PharmData’s analysis also illustrates variation across England, with the London region doing worst and the North West best (Figure 1, left), although that will be cold comfort to pharmacies in the North West: with 1,532 pharmacies and a total of 73,581 CPCS referrals for the year, that’s just 48 on average per pharmacy. It’s likely some pharmacies got no referrals at all, which begs the question about whether they’ll want to continue offering the service when there is no payback.

CPCS referrals are not at the scale that can really make a material impact on the NHS at the national level at present. There is likely still to be a big gap between the scale of CPCS and the opportunity to both ease the pressure on the NHS and reward the unpaid informal consultations community pharmacies deliver.

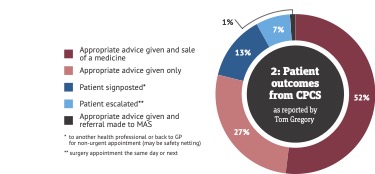

As for the issue of waste, there are pharmacists tweeting their experience. Tom Gregory, a GP practice pharmacist working in North Somerset, tweeted on the 14 June this year that the GP practice made 21 CPCS referrals in one day. That rate puts them far ahead of many others. A breakdown he gives suggests that relatively few patients seen via CPCS (13 per cent) were signposted to another healthcare professional or back to the GP for a non-urgent appointment (see Figure 2).

That’s not far off the reported figure of 90 per cent of all referrals across England being completed within a single episode of care over 18 months, according to Anne Joshua, NHS England’s head of pharmacy integration.4 An impressive 97 per cent of patients reported that they would use the CPCS service again.

The fact that patients are willing to take up community pharmacy consultations once referred, that the consultation can resolve the issue in the vast majority of cases, and that patients would use CPCS again means that despite the opportunity to reduce pressure on the NHS largely remaining unrealised so far, there are encouraging signs.

The fact that patients are willing to take up community pharmacy consultations once referred, that the consultation can resolve the issue in the vast majority of cases, and that patients would use CPCS again means that despite the opportunity to reduce pressure on the NHS largely remaining unrealised so far, there are encouraging signs.

But there remains a policy question: do the incentives need to be revisited to get CPCS to deliver on its potential?

References

1 PSNC. (May 2021) Pharmacies in England carry out 58 million consultations a year. Retrieved from: https://psnc.org.uk/our-news/pharmacies-in-england-carry-out-58-million-consultations-a-year/

2 PSNC. (May 2021) PSNC Pharmacy Advice Audit 2021: 2021 Full Report. Retrieved from: https://psnc.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/PSNC-Pharmacy-Advice-Audit-2021-Report.pdf

3 PSNC. (June 2020) CPCS referrals hit 300,000. Retrieved from: https://psnc.org.uk/our-news/cpcs-referrals-hit-300000

4 Pulse. (April 2021) One in 10 online GP consultations could be referred to pharmacies under new scheme. Retrieved from: https://www.pulsetoday.co.uk/news/workload/one-in-10-online-gp-consultations-could-be-referred-to-pharmacies-under-new-scheme/