Is it too tempting to claim big?

In Insight

Follow this topic

Bookmark

Record learning outcomes

By Leela Barham

The Pharmaceutical Services Negotiating Committee (PSNC) has a tough job in advocating and negotiating for the sector. It is not alone in trying to capture the attention of Ministers; it’s just one of many groups that civil servants at the Department of Health and Social Care and NHS England regularly engage with. Let’s not overlook Her Majesty’s Treasury. If they’re not in the room, they get briefed afterwards.

There is little routine reporting of what community pharmacies do, beyond the basics of dispensing. That visibility problem is tough to overcome, given there is no right or wrong way to go about advocacy and negotiation.

PSNC published the findings from its latest ‘audit’ of advice delivered by community pharmacies with the headline “Pharmacies in England provide 65 million consultations a year.” The press release highlights how grossing up results of the ‘audit’ means 117,000 informal referrals a week across England, all of which “could and should have been made by the NHS Community Pharmacist Consultation Service (CPCS).”

That lays bare how the results are part of a bid for more funding, perhaps not directly, but as an effort to get referrals working as they should, which would boost income on the pay per consultation basis of CPCS. That funding bid is shored up by arguing that without community pharmacy, the NHS would be under more strain than it already is. Community pharmacies are delivering added value without getting paid for it. Sadly, it’s a familiar state of affairs; much of the NHS runs on “freebies”.

The ‘audit’ has value; P3pharmacy nailed it when it said it would strengthen the hand of PSNC in government talks. But there are weaknesses in the study. Being upfront about these could make for a more compelling case.

Respondent fatigue

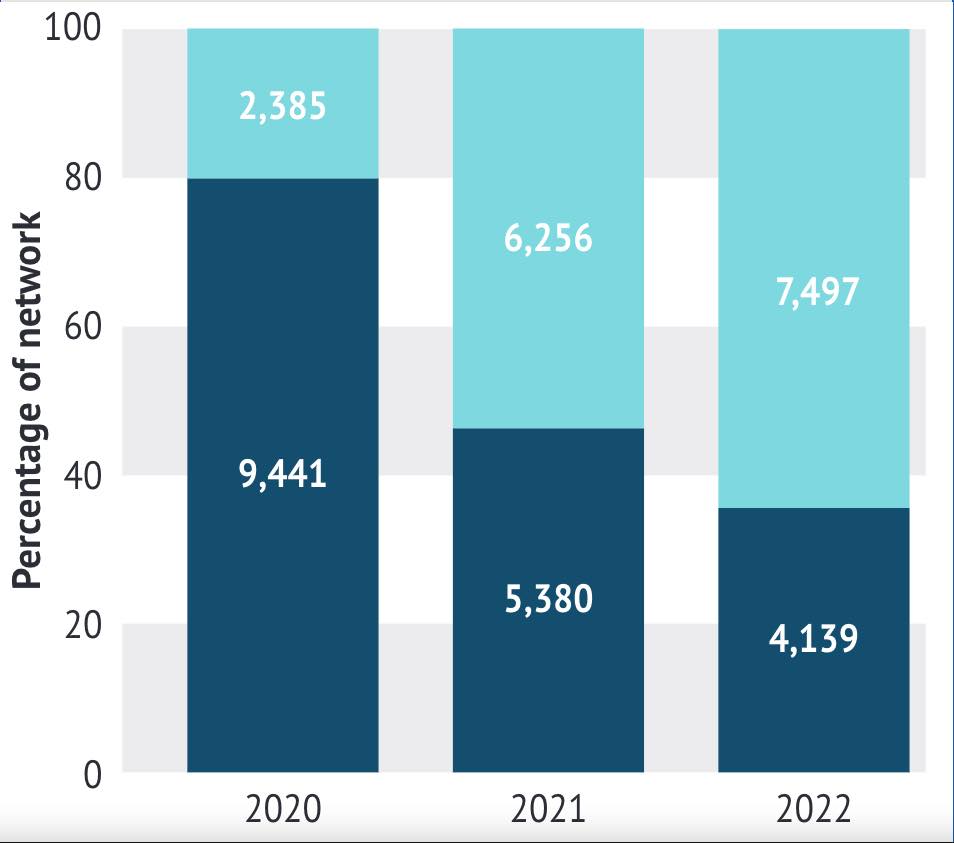

Some 4,139 community pharmacists took part in the winter 2022 audit. This is 38 per cent of the 10,800 pharmacies PSNC uses as the size of the network (distance selling pharmacies are excluded). A response from two in five community pharmacies is not so impressive and is even less so when compared with the numbers participating in the past (Figure 1). The 2020 audit covered over 80 per cent of the network; that fell to just below 50 per cent in the 2021 edition.

Note: baseline network 11,436 in 2020 and 11,264 in 2021 and 2022 differs to PSNC figures. Impact 1-2%

There isn’t enough on the nature of the respondent pharmacies to explore whether they differ from those who did not respond. Serial non-respondents are likely to be different to respondents, even if it’s no more than having an aversion to completing surveys. Identifying what’s driving the drop off in response is a challenge; anecdotal evidence would suggested it is fatigue with the audit itself, but given the evidence that community pharmacies are doing more, perhaps they simply cannot spare the time. Unfortunately, it’s a question those they want to influence are likely to ask.

Representativeness

PSNC’s report of the audit is also silent on where the 4,139 community branches that took part are located: it’s unclear whether this is because they don’t know or have chosen not to say. Since they are able to identify community pharmacies that have consistently completed the survey, the latter is more likely.

Whether the participants are geographically representative might matter because there is evidence that access differs by urban and rural location. There is also evidence* that provision of advice on prescription medicines (not covered in this audit) can vary by ethnicity; it would be surprising if there wasn’t variation when it comes to other advice. It could also be a missed opportunity: tackling health inequalities is a big focus of the Government’s levelling up agenda.

GP appointments saved

After extrapolating its findings, PSNC suggests community pharmacies “save 32m GP appointments every year.” NHS England says general practice delivers over 300m consultations a year. The latest data from NHS Digital – from July 2021 to June 2022 – puts the figure at over 376m appointments. That makes 32m consultations equivalent to around 10 per cent of appointments in practices, which is material, making contextualising the estimate from the audit even more important.

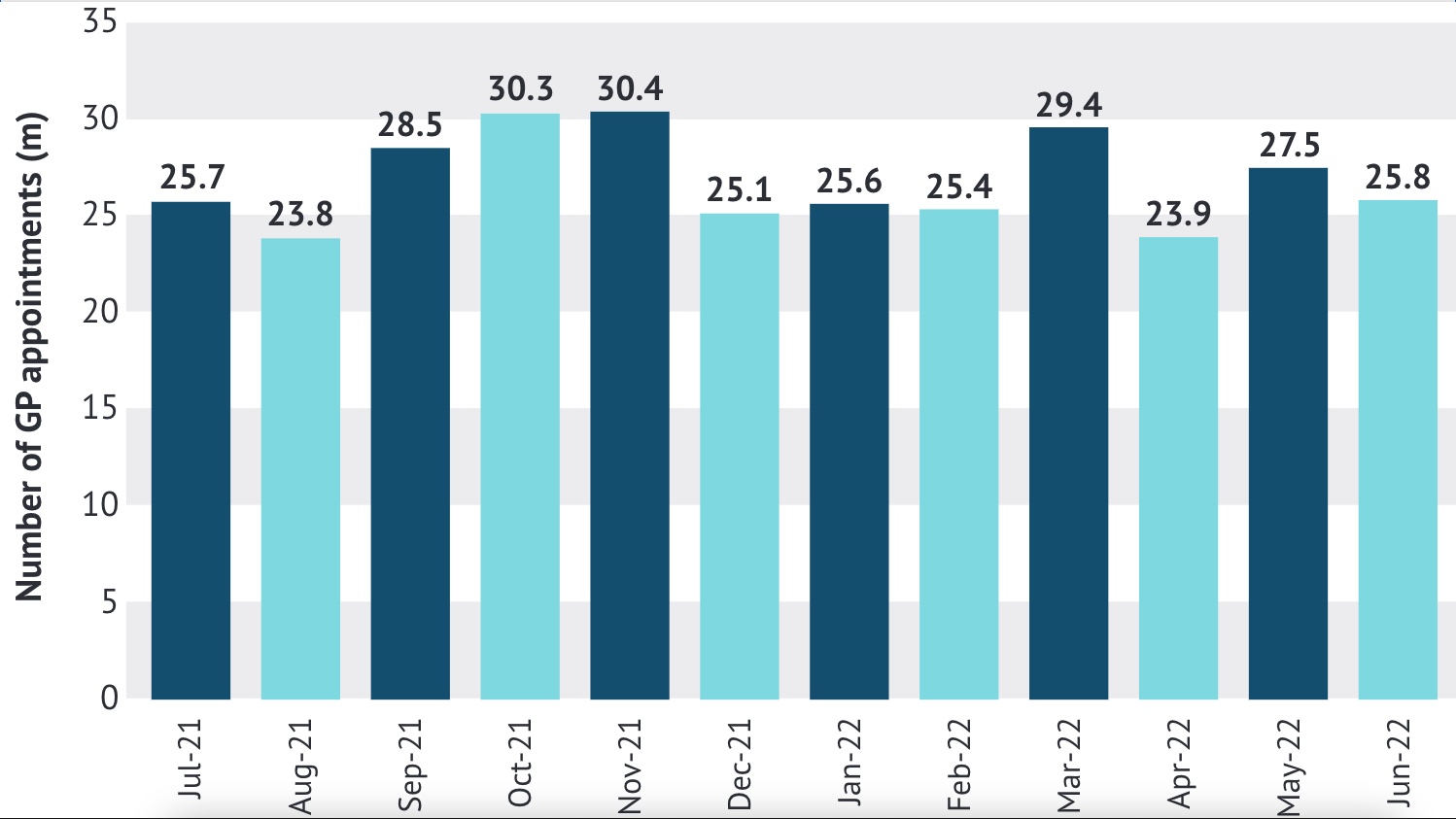

For example, activity in GP practices varies. In the past year, more than 30m appointments were logged in the busiest month (November), compared with 23m in August, the quietest (see Figure 2). Seeking advice from community pharmacy could vary over a year too, making the timing of the audit material. Was it a high or low consultation month? Does it matter that it was possible to complete the audit in a few days (as long as the minimum of 20 consultations was hit)? The audit was run in winter, but January was a ‘low’ GP appointment month. Could potential appointments saved be an underestimate?

The potential for days of the week variation is also ignored. More community pharmacies (482) filled in the audit on a Monday, but only 42 on a Saturday. It’s impossible to know if there are systematic differences by pharmacy according to the day of the week, but there is a variation in average consultation per day from 24.6 (Wednesday) to 30 (Saturday).

Patients were asked at the pharmacy what they would have done had the pharmacy option not been available. Obviously, seeking a GP appointment scores highly, but that question is asked without any of the trade-offs required to take action, such as the time and hassle of getting that appointment. We know from the headlines that it can be hard to get a practice appointment – although NHS Digital numbers show appointments continuing to rise – but it’s easy to say what you would do, harder to do what you say. Arguably, 32m could be an over-estimate.

Extrapolating for a year is tempting, but it’s hard to overcome the basic issue that the audit is a snapshot. It’s an oversight to not caveat the report. Given the number of uncertainties, it may be better to present ranges for impact, rather than point estimates. Even the lower end of the range is likely to be a big number.

Survey, not ‘audit’

I’ve used ‘audit’ in this article because PSNC doesn’t actually run an audit; readers will be familiar with the independent nature of audits conducted for finance purposes. That’s not to suggest the results are not true, but it’s arguably better simply to be clear about this from the start.

Audits in healthcare, including clinical audits, will typically have some independence built in. An independent group will analyse the results and may undertake some validation when the data comes from those delivering the service. Outcomes also tend to be set against explicit benchmarks and geared more at quality improvement. These elements are just a small part of the PSNC ‘audit.’

Since PSNC has used ‘audit’ for years, it’s a hard term to drop, yet it means that a mismatch between what civil servants might expect an audit to mean and what PSNC actually does is possible. Better to tell it like it is and go with ‘survey’?

Process is just process

The PSNC ‘audit’ measures process. It matters that patients can access the care they need and that’s often good for the NHS too, where it means more expensive care is avoided. The audit hints at outcomes, by looking at proxies for severity, with 17 per cent of patients referred to a GP practice, of whom 23 per cent were deemed to require urgent assessment. Close to 5 per cent were referred to A&E. Presumably these are the patients who might otherwise have become more poorly; some could have needed more (expensive?) support from the NHS.

However, that’s tough to reconcile with an average of 5.6 minutes for a consultation; wouldn’t patients who are ill require more time, even in a community pharmacy? The report does present a range of consultation times, revealing some going beyond 15 minutes, which is helpful.

Teasing out whether patients are healthier as a result of the community pharmacy intervention is ultimately what matters. Shouldn’t we ask them? The same logic applies to the value patients place on community pharmacy.

Next time improvement

As the exercise is seen as useful in negotiations, a repeat is likely. It would be a help if those who do not take part could be asked why. It’s essentially a prisoner’s dilemma. The best for everyone is when everyone does their bit. It’s not clear, for example, whether those who put in the time do more than those who freeride on others. PSNC could also consider the context and caveats too; ranges would make them a more honest broker.

Community pharmacies could well be doing more – but maybe less – than the averages and extrapolations suggest, but whatever they are doing should be presented with the best chance of being accepted as accurate (as the methodology permits).

REFERENCE

* Rivers, P.H. et al. (2017). Exploring the prevalence of and factors associated with advice on prescription medicines: A survey of community pharmacies in an English city. Health & Social Care in the Community. 25 (6) pp.1774-1786.