Setting a baseline to assess the impact of the five-year deal

In Running Your Business

Follow this topic

Bookmark

Record learning outcomes

By Leela Barham

The 2019/20 – 2023/24 Community Pharmacy Contractual Framework (CPCF) was the first five-year deal struck between the Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC), NHS England & NHS Improvement (NHSE&I) and the Pharmaceutical Services Negotiating Committee (PSNC).

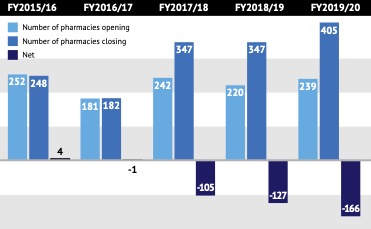

One of the ambitions of the deal was to help support investment in community pharmacy by providing a period of stability. While they don’t tell the whole story about investment, the numbers of new community pharmacies opening suggest a willingness to invest. Closures suggest the opposite. They signal that a pharmacy is no longer viable as a business, at least in the eyes of those selling up. The numbers of community pharmacies that stay open gives a signal about stability: these are viable (at least for now) and may even receive investment themselves or contribute cash to help with expansion.

With statistics from the NHS Business Services Authority (NHSBSA) only available up to the end of the 2019/20 financial year, it’s too soon to use these to explore how stable the network has been since the contract started that year. But the November 2020 data release sets the baseline for future assessments of stability, and can help to set out the scale of change that the network experienced before the contract came into place. Less volatility is another useful signal, although, of course, the 2019/20 statistics also pre-date the pandemic.

The community pharmacy network in England has been relatively stable. It has seen a net decline from 2015/16, but the magnitude is still small – from 11,949 branches in 2015/16 to 11,826 in 2019/20 (a 1 per cent fall). However, the direction of travel could be a concern, with openings not enough to offset closures in four of the past five years (Figure 1, above).

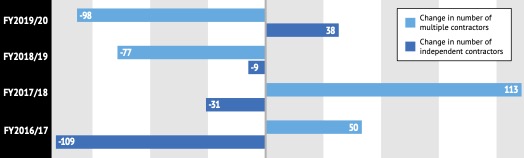

Shares in network shifting

At a national level, the share of community pharmacies run by independents and multiples has held steady at around 40:60 respectively over the period 2015/16 to 2019/20. Up to 2017/18, there was a small growth in multiple-owned pharmacies and a corresponding small decline in the number owned by independents. This reversed in 2018/19 and 2019/20, suggesting multiples are consolidating and independents are either coming into the market or existing independents of up to four branches are expanding (Figure 2, above).

The independent/multiple split also highlights a gap in terms of how far we can use NHSBSA data to make sense of what is going on in the market. It puts the cut off between independents and multiples at six pharmacies. However, the economics must surely be different for different sizes of multiples.

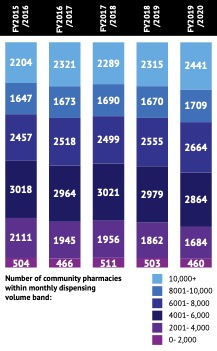

The flip side of closures could be that the remaining community pharmacies are becoming more sustainable – either by paying their own way or via cross-subsidies from more profitable branches.

PSNC has said that some independent pharmacists face losing their businesses

Whilst subtle, there has been a shift towards larger dispensing volume pharmacies, with fewer branches with monthly dispensing volumes in the 0-2000, 2001-4000 and 4001-6000 bands from 2015/16 to 2019/20. There are also more in the 10,000+ band (Figure 3, below).

There has also been a growth in the number of prescription items dispensed and the value of fees over the 2015/16 period, so that there is more to go around fewer community pharmacies (the average number of prescription items dispensed per community pharmacy was 83,295 in 2015/16 rising to 87,254 in 2019/20). With a growing population in England, there are also more people per community pharmacy branch: up from 4,585 to 4,760 people per branch between 2015/16 and 2019/20. That’s the national picture, of course; local circumstances will vary markedly across England.

Beyond the statistics

The NHSBSA data can help to identify changes in the network, but it cannot provide insights as to the reasons for changes. We need to look to other sources for that, such as companies who support the buying and selling of pharmacies.

As P3pharmacy reported in January, specialist business property advisor Christie & Co provides a perspective on who is selling and who is buying community pharmacies. Its view is that there are new investors coming in, including private equity and those with access to private equity, as well as independents who are spotting opportunities.1

Lincoln International, an investment advisory firm, has pitched community pharmacy as a promising investment opportunity. This is partly because the value of the network has become clearer as a result of Covid, and the sector has fared well versus other places in potential investment terms.2

The NHSBSA data is also retrospective – we only have up to the end of 2019/20 so far. More recent warnings about the future have been dire. PSNC has said that some independent pharmacists face losing their businesses,3 while analysis commissioned by the National Pharmacy Association last September predicted that around three-quarters of independent pharmacies could be in deficit by 2024.4

Gaps in evidence

More may yet emerge about the workforce. A Health Education England (HEE) survey ran from 7 May to 18 June 2021 and should give some insights into who was working in the community pharmacy team, as well as recruitment experiences and working patterns.5 This aims to inform future planning and system investment decisions.

But what is needed to help understand the impact of the CPCF is whether community pharmacies have been able to not only run but to go further and invest in staff. That looks like a gap that needs to be filled to set out the scale of investment in people, who are vital to the successful delivery of community pharmacy services.

Similarly, the NHSBSA data doesn’t help us to understand the current fabric of branches. Just how many are in need of refurbishment? No doubt some changes happened fast within branches to help manage the risk of Covid – the installation of screens, for example – but that does not imply there is no need for further investment in the fabric of community pharmacy.

The contract sought to provide stability so that community pharmacy could invest. That’s a laudable aim, but there is a need for more evidence to assess this so that both sides – government and community pharmacy – can tell what’s been achieved and what should change to inform future arrangements.

Only bringing together material from a variety of sources – facts as well as sentiment – will provide a fuller understanding of investment that has been delivered and what is needed to maintain the incentives for investment in the future.

Data, all figures: 'NHSBSA General Pharmaceutical Services - England 2015/16 to 2019/20', published November 2020