In Long term conditions

Follow this topic

Bookmark

Record learning outcomes

Past civilisations have a lot to tell us about the causes of dementia. Perhaps we should start listening.

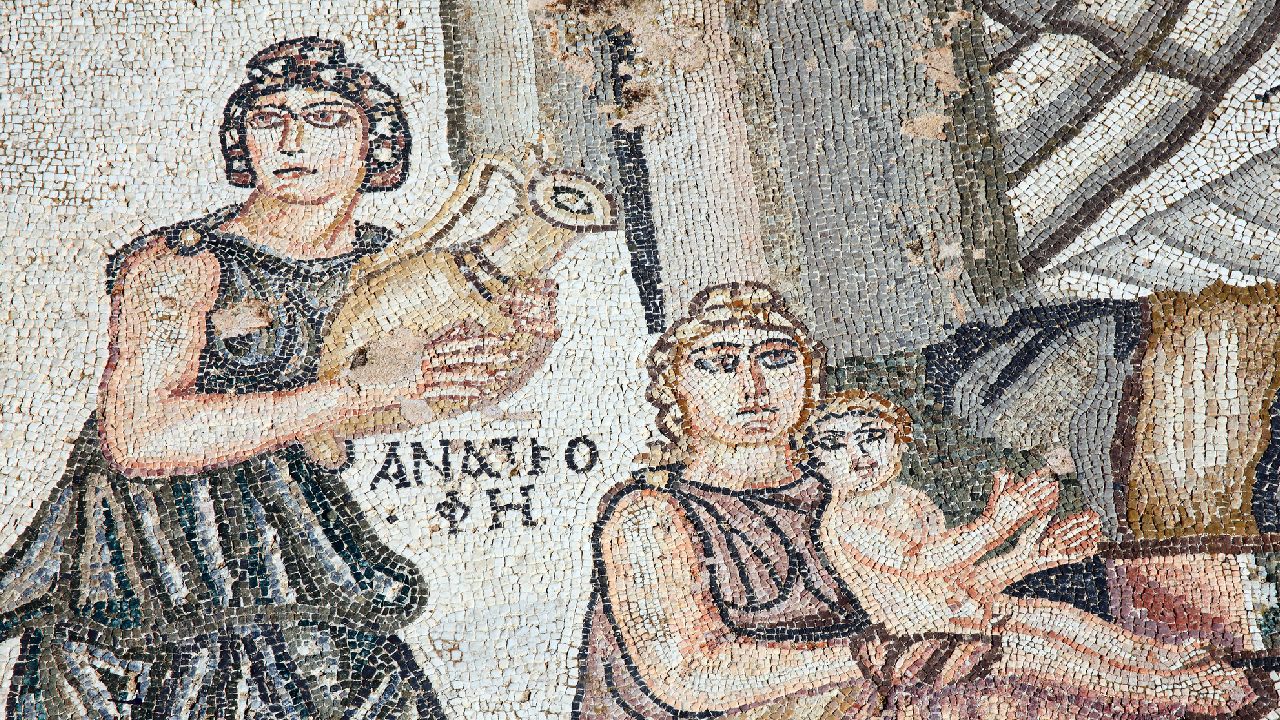

Ancient Greco-Roman authors and studies of the Tsimane, an indigenous people in Amazonian Bolivia, have lessons for industrialised societies struggling to cope with rising rates of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and related dementias (ADRD).1

“Historical and ethnographic perspectives suggest that, in addition to whatever personal genetic or other characteristics AD patients may have, environmental factors play a role in the aetiology and incidence of AD,” says Dr Stanley Burstein, professor emeritus of history, California State University, Los Angeles, and co-author of a new paper.1

“The evidence, limited though it is, suggested that for much of ancient history AD incidence was not constant but varied due to multiple factors in the lived environment.”

Stereotypical evils of old age

Greco-Romans expected, despite some memory loss, “intellectual competence” well beyond the age of 60 years.1 “The ancient Greeks had very, very few – but we found them – mentions of something that would be like mild cognitive impairment,” says co-author Professor Caleb Finch, Leonard Davis School of Gerontology, University of Southern California.

“When we got to the Romans, we uncovered at least four statements that suggest rare cases of advanced dementia – we can’t tell if it’s AD. While these cases were rare, this suggests an ongoing increase from the ancient Greeks to the Romans.”

In the early second century AD, the poet Juvenal included memory loss “among the stereotypical evils of old age”.1 “Juvenal’s use of dementia [which means ‘out of mindedness’] to describe severe elderly memory loss … suggests greater awareness of that condition among elite Romans in his time,” Burstein and Finch write.1

Pollution from charcoal burning may partly underlie the possible increase in advanced ADRD during the Roman era.1 Today, air pollution may increase AD risk by triggering inflammation, oxidative stress and beta-amyloid deposition.2

Meanwhile, Romans sweetened wines with sapa, grape juice boiled in lead vessels. Lead pipes carried water. Romans cooked in lead vessels. Women used leaded cosmetics.1 Not surprisingly, Roman skeletons show high lead levels in bones and teeth.3 Lead seems to stimulate beta-amyloid deposition and tau filament production.1

“We suggest lead pollution as one such possible factor in antiquity but certainly not the only one or not even the most important one,” Professor Burstein says. “Greeks and especially Romans encountered lead in every aspect of their lives, and that is likely to be the case with other such factors that may be involved in AD.”

Lessons from Bolivia

Further evidence supporting the importance of environmental ADRD risk factors emerged by studying the Tsimane. Professor Margaret Gatz, with Finch and colleagues, found that only 1.2 per cent of Tsimane aged 60 years and older develop dementia. All the dementia cases were mild and were not clinically consistent with AD.4

In contrast, the Alzheimer’s Society estimates, in 2019, 7.1 per cent of people aged 65 years and over had dementia in the UK. Of these, 27.8 and 57.7 per cent had moderate and severe dementia respectively.5

Brain imaging studies comparing Tsimane, Europeans and Americans suggest that industrialised lifestyles increase the rate of age-dependent brain volume decreases by about 70 per cent, despite higher levels of inflammation (e.g. from infections).6 In other words, the brain shrinks as we age – but the decline is slightly faster in industrialised societies.

Tsimane, who survive by subsistence farming and foraging, typically show low HbA1c and cholesterol levels, blood pressure and obesity rates (partly because of parasite infestations and frequent infections). So, cardiovascular disease, which is intimately linked with ADRD, is rare.7 About 80 per cent of AD patients in industrialised countries have vascular disease.8

According to the Alzheimer’s Society, at least one in 10 dementia patients has mixed dementia, usually AD and vascular dementia.

Greco-Roman physicians recognised that good health builds on the foundation of prevention. Two millennia later, preventing dementia remains better than amyloid-clearing drugs, for all their pharmacological sophistication. ADRD prevention means addressing environmental risks generally and cardiovascular disease particularly.

“The Tsimane data is very valuable,” Professor Finch concludes. “This is the best-documented large population of older people that have minimal dementia, all of which suggests that the environment is a major determinant on dementia risk.”

References

1. J Alzheimers Dis 2024; 97:1581-1588

2. Nat Rev Neurosci 2023; 24:129-130

3. J Anc Civ 2022; 37:225-246

4. Alzheimers Dement 2023; 19:44-55

5. Available at alzheimers.org.uk/sites/default/files/2019-11/cpec_report_november_2019.pdf

6. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2021; 76:2147-2155

7. Lancet 2017; 389:1730-1739

8. Prescriber 2019; 30:13-16