From pixels to population health

In Interviews

Follow this topic

Bookmark

Record learning outcomes

Yonatan Adiri doesn’t code. That, together with his passion for public service, make him a somewhat unlikely tech entrepreneur. But thanks in part to NASA and Kim Kardashian, he’s on a mission to transform the smartphone camera into a clinical grade medical device. What began with a call from his dad, has quickly turned a start-up into a company scaling up globally.

Yonatan Adiri doesn’t code. That, together with his passion for public service, make him a somewhat unlikely tech entrepreneur. But thanks in part to NASA and Kim Kardashian, he’s on a mission to transform the smartphone camera into a clinical grade medical device. What began with a call from his dad, has quickly turned a start-up into a company scaling up globally.

By Rob Darracott

The call was from China, where his parents were on holiday. His mother had had a fall, and lost consciousness. “The four of us brothers in Israel had to figure out what to do,” says Yonatan Adiri, the founder and chief executive of Healthy.io, creators of the ground-breaking Dip UTI test kit and app that delivers clinical grade urinalysis via smartphone. “My father was saying ‘they say she broke her ribs and I’ve seen people who’ve broken their ribs and that doesn’t look like it. They want to fly her to Hong Kong in two days’. Luckily, they bought an iPhone 4S before they flew out. I don’t know what would have happened if they hadn’t.”

Yonatan asked his father to take a picture of the CT scan with the iPhone and send it to him. “I had on speed dial one of Israel’s top trauma doctors” – a legacy from his days working for former President of Israel, Shimon Peres. “I texted to ask him to take a look at those CT scans - they want to fly her to Hong Kong, they think it’s just some fractured ribs. Literally within five minutes he texted me back. ‘No, no, that’s pneumothorax, she has a punctured lung, one of you four should fly in and spend a couple of weeks with her, she’s not going anywhere. She can die while taking off.’ My brother flew out, stayed with my mother for 10 days. They flew direct back to Israel; she’s fine, it wasn’t a big deal, then I realised, we might just have saved her life, and without inventing a new technology. We just took some pictures and sent them to people.”

That lightbulb moment was the spur for Yonatan to take, as he puts it, a deep dive into healthcare. “Healthcare to me was always out of bounds. I’m not a doctor, I’m not an engineer, but suddenly it became a lot clearer to me that there is a lot we can do, while we wait for the next penicillin moment, the before/after moment we had in the 20th century. It will happen in the 21st century, but in the next 20 years it’s incumbent upon us who are not doctors to make a difference as much as we can.” The result was Healthy.io. Its mission: to be the company that transforms the smartphone camera into a clinical grade medical device.

For a member of Time magazine’s “50 most influential people in health care of 2018”, Yonatan does not have the typical career path of a tech entrepreneur. “I don’t code. I’m not the tech person in the company,” he says. “I dedicated most of the early years of my career to the public service, which is still where my passion lies, and which is why we develop products focused on population health.”

Now 36, he's the youngest son of refugees to Israel in the 1950s, one from Iraq, the other from Tehran in what was then Persia. “My parents spent seven years in a refugee camp in Israel, when the country was slowly evolving. They made a decision to do whatever they needed to do so that we would have access to education, the most important thing for them and a path to safety.”

At 14, a junior high school teacher advised Yonatan to take an Open University course a day a week. He graduated with a BA at 17, and then, like all Israelis, completed national service in the military, where he was the chief negotiator for the army with the Red Cross. A period of research in the US followed, after which he landed, at 26, the role of chief technology officer for President Shimon Peres, then 86 and a founding father of the country. He recalls calling his father, who had a deep respect for Peres owing to his rising to prominence as a politician in the 1950s, to tell him. “You are going to advise Shimon… on what?” his father asked.

Working for the president, and attending NASA's experimental university

He describes the four years with Peres as “a real privilege. He had a profound understanding of technology and where it would lead us.” The time was significant. “It designed my thinking around tech, we were discussing where healthcare was going, bioinformatics, neuroscience, stem cells, immunotherapy, but I never at any moment thought of myself as a person who would play a role in this industry as an entrepreneur. I spent time in the White House, and in the Blue House in Korea, working with Israel’s partners on long term tech development.” Peres stood out. “As a society now we have no technology statecraft,” he says. “Today’s leaders don’t really understand where tech is going and what it means. A great example was the senate hearing of Zuckerberg. You saw people ask questions of no importance, yesterday’s questions. But Peres understood it, because he had seen things like that time and time again.”

In 2009 President Peres sent Yonatan to a NASA-hosted 100-day training session in Silicon Valley. “It was the moment I started considering being at the front of this, as opposed to being an adviser, or working with people on how to change things.” The idea was to expose an experimental class of 30, drawn from across the world, to the exponential growth of technology. “We all knew about computation doubling every two years, but the same was happening to bandwidth, battery quality, camera sensors, GPS location. What kind of initiatives come out when a group of interdisciplinary folks from around the world understand that if something is at a capacity of 100 right now, in three years it’s not going to be at 105, 107 or 110, but at 600 or even 1,000?”

On a trip to Stanford the group was introduced to the autonomous car. “We saw the car that won the DARPA challenge in 2006 [the competition for self-driving vehicles run by the American defence industry]. And we realised, that between 2006 and 2009, the car that won, the big 4x4 with all the sensors was now a Toyota Prius with a small thing on the top. The exponential curve had hit many levels: bandwidth, computation, sensors, data processing in real time, stuff that was on the car in 2006 was now on the cloud.”

From concept to start-up

Five of the group started thinking. “Within 10–15 years autonomous cars are going to be on the road, and when that happens, will mobility go the way of data? Cars are going to drive on their own, we’re going to route people by calculations, like packets, like we did with data and TCP/IP. And how many of the 300 million cars in the US do you actually need for everyone’s mobility needs without sacrificing any latency? A third of the cars. “We’re not car engineers or computation experts, but Zipcar were about to IPO for a billion dollars. It had 10,000 cars parked in major cities. Airbnb allows people to rent out their room; why wouldn’t people rent out their car? That was the first time I took an idea from conceptualising it to giving birth to a company.

Yonatan says there are parallels with his new business. “Healthy.io will not solve cancer, much like Getaround.com did not bring the autonomous car. But at the crucible moment for Healthy.io, I understood that enough exponential curves converged to allow for a product that would make the lives of many people easier, while not asking them to buy something new.”

We’re in a modern meeting room in a London hotel. Whiteboard walls. Yonatan gets up to sketch a graph. Growth over time. Battery quality, an exponential curve right. Sensor quality, steeper. Camera quality, steeper too. “It was very clear in 2013/14, when you get to 2016 those phones are going to be as good as medical devices,” he explains. “Kim Kardashian asked her 30 million Twitter followers to tweet a picture of a garment. Twenty-five per cent of all images on Twitter that day – 100 million pictures – were because of Kim Kardashian. This trend - the move to social media by pictures (Instagram, Snapchat) was going to intensify. We called it Kardashianomics. If Apple realises iPhone sales are going to depend on the quality of the camera, then we are going to have amazing cameras. So, not only is this thing going to turn into a clinical grade medical device, it’s going to happen faster than we think. That’s the premise behind Healthy.io.”

We’re in a modern meeting room in a London hotel. Whiteboard walls. Yonatan gets up to sketch a graph. Growth over time. Battery quality, an exponential curve right. Sensor quality, steeper. Camera quality, steeper too. “It was very clear in 2013/14, when you get to 2016 those phones are going to be as good as medical devices,” he explains. “Kim Kardashian asked her 30 million Twitter followers to tweet a picture of a garment. Twenty-five per cent of all images on Twitter that day – 100 million pictures – were because of Kim Kardashian. This trend - the move to social media by pictures (Instagram, Snapchat) was going to intensify. We called it Kardashianomics. If Apple realises iPhone sales are going to depend on the quality of the camera, then we are going to have amazing cameras. So, not only is this thing going to turn into a clinical grade medical device, it’s going to happen faster than we think. That’s the premise behind Healthy.io.”

Yonatan says that in terms of vision, Healthy.io is no different to many digital healthcare companies. “We all see that we will not consume healthcare as we always have; our mission, though, is unique. We want to be the company that transforms the smartphone camera into a clinical grade medical device. We want to be the best in class, the first through a clinical trial in Europe, in the US. No hardware needed. If I ask you to buy a $100 lens, I exclude most of the population.”

Healthy.io’s strategy has three key principles. Products must be of clinical value, have the potential to reach large numbers of people, and be computer vision based. “We don’t want to reinvent or disrupt. We don’t want to be outside the existing pathway,” Yonatan says. He explains: “Four years ago, at the height of wellness and wearables, I couldn’t raise capital. The folks doing medical devices were ‘where’s your hardware?’. The digital folks were ‘FDA trials? That’s not for us’. But we want to be a player that enhances population health; that’s where we want to make a difference.” As for the third: “That’s what we know; we know artificial intellingence and we know computer vision very well.

“We zoomed in on urinalysis because it satisfied all three. It’’s been going on for the last 50 years, doctors love it, it’s an early line of defence, for UTI, pregnancy, diabetes. The clinical evidence is very clear; the cost curve is already down. Dipsticks are cheap, you can train an algorithm. From an operational perspective we don’t need a lot of capital. It’s the second most used IVD [in vitro diagnostic] after blood counts, and from a computer perspective, the technological question is very simple: can you teach a smartphone camera to read colour as good as a lab device? It’s a tricky question, because colour is always a function of light.”

However, Yonatan and his team suffered an early setback two years later, when a clinical trial failed 200 patients in. He feared two major risks – his primary investor, Iden Ofer, would pull out, or his top talent would be lured away by the world’s tech giants, Google, Apple, Intel, whose own computer vision operations are on the company doorstep in Tel Aviv. Fortunately, the investor doubled down, and the team, led by long-time chief product officer Ron Zohar, stayed on board too, stepped up and led the resolution.

‘If you can text, you can test’

The issue was the algorithm or the app. “There was a challenge to the algorithm, for sure, but the main problem was usability 100 per cent. We had a brilliant 20 second video. Watch it, pee, dip, scan. The only problem. Men, mainly men, didn’t watch the video. The product design is so simple, cup, stick, people thought they knew it. They skipped the video.” The result: tests were not completed properly.

The answer, Yonatan says, was ‘Ron’s credo’. “If someone can text, they can test.” The app was redesigned to mimic a series of texts. He opens the app on his phone. “I’m going to have to click six buttons, over two and a half minutes. That’s what gets people to do the test right. This works 99.5% of the time; only one out of 200 people in the clinical trial failed.” He says it’s complex to deliver real clinical value, where it’s about people, in the digital domain, and not many companies have succeeded in doing it. He cites Livongo and AliveCor as notable exceptions.

The answer, Yonatan says, was ‘Ron’s credo’. “If someone can text, they can test.” The app was redesigned to mimic a series of texts. He opens the app on his phone. “I’m going to have to click six buttons, over two and a half minutes. That’s what gets people to do the test right. This works 99.5% of the time; only one out of 200 people in the clinical trial failed.” He says it’s complex to deliver real clinical value, where it’s about people, in the digital domain, and not many companies have succeeded in doing it. He cites Livongo and AliveCor as notable exceptions.

He shows me a letter from a kidney transplant patient from Salford (the product is being used by the NHS there to screen for UTIs, a particular danger because of the necessary immunosuppression. “Symptoms over Christmas, did the test, called 111, within an hour had the antibiotics. Possibly saved her hospitalisation, or an immune system crash.”

I ask Yonatan to summarise where he sees the product now, three weeks into the first trials in a community pharmacy setting, in 37 Boots stores across England. He has a ready answer. “First, we have created a category. Smartphone urinalysis, clinical grade is a reality for pregnant women in Israel, for diabetics in the UK, for transplantees. Second, we have a clinical evidence base that assures the system this is within the pathway.” Trust is important. “The reaction of most incumbents is negative. Getting through the FDA is just the start.” Third, there is clinical evidence. He says 80 per cent of people at risk of kidney degradation in the US have not had a urine protein check (albumin to creatinine ratio) in the past year in spite of follow up efforts. “Mind boggling, right? When you get symptoms it’s too late.”

The US National Kidney Foundation commissioned Healthy.io to work with the Geisinger Health System in Pennsylvania to look at 1,000 people with diabetes and hypertension. Half got standard care, half received what Healthy.io calls ‘adherence as a service’, starting with a text message inviting them to receive a test delivered to their homes. When the data was examined, 71 per cent in the Healthy.io arm completed a test against 17 per cent on standard care. A number of tests were positive for protein.

“From this evidence base, I can go to a commissioner and say, ‘don’t pay me in advance, just pay for protein’,” Yonatan says. “The US clinical guideline is $1,800 if you find protein in the urine because the preventive mechanism is solid. The business model allows you to take no risk in day one, invest in prevention without spending capital, but committing to pay me for every protein found from the savings you will get from day one.”

Fourth is patient focus. “We enable nurses, pharmacists, commissioners, but the end of the journey is the user,” Yonatan says. Healthy.io currently boasts a net promoter score (NPS) of +70, outperforming top US retailers, airlines and the rest of the health sector. “That’s a big deal – people who have worked with the product don’t want to go to the lab anymore, and they would recommend it to others.” He says that among the Hispanic population in Baltimore, who won’t attend the world-famous Johns Hopkins Hospital for cultural and language reasons, the Spanish-speaking Healthy.io app rates an NPS of +90.

Lastly, there is sharing the story. “We’re inspiring other entrepreneurs to go into this domain – we’re super happy to share the lessons,” Yonatan says. “The key to all five elements is empathy,” he adds. “Delivering healthcare to a population is hard. Start-ups like to move fast, but we recognise why doctors, nurses, commissioners have to be conservative. Maybe because I came from the public service my thinking process was not pure tech – ‘this works, why is everyone so stupid they can’t see that?’ Change is complex; commissioners have challenges. It’s incumbent upon us, the start-up, to adapt our offer, service, language, to the person on the other side. Things we think will take 90 days take 9–12 months.”

“I get asked a lot, by our board… there’s revenue, there’s people, there’s great NPS, there’s partnership. What’s the risk? I say for a company to succeed a company needs scale. It needs to sell in a way that allows us to innovate – we’re a research company.”

In 2019/20 that challenge is going to be training. “We are a business to business (B2B) and a business to consumer (B2C) company – we sell to the NHS, or Boots, or an HMO. The training of those people who will end up interfacing with the consumer is where we need to grow. Building the right digital spec, that would have the pharmacist in, say, Southampton, log on and have a great 10-minute experience on a smartphone, to make them super-likely to be empathetic to the person who comes in and consumes the product.”

Yonatan stresses the pilot nature of the test and treat trial for urinary tract infections with Boots. “This collaboration in the last couple of months has helped cement the fact that this is a category. I’m very excited to engage with Boots on a broader conversation when the time comes.” He’s complimentary about the company’s approach. “They’ve been incredible in adhering to all the protocols, taking zero risk. Their conservative approach has safeguarded us. The way they built the PGD, trained their people, the way they start in certain stores, so they can demonstrate antimicrobial stewardship. We’ve learned a great deal, which is what pilots are about.”

Strategic outlook at national level

As for next steps? “There is a business model. It saves the doctor’s time, it makes sense for the patient, the pharmacist and the system. We have a product line, do we want to make this a clinical reality, in Berlin, Paris. Do you do it yourself, or go into partnership?” And the big question, which his journey so far equips him perfectly for, the strategic outlook. “Does ‘UTIs should not be treated in the lab within eight years’, work as a roadmap for a conversation at national level? I can imagine two years from now, all 1.5 million people with diabetes in the UK getting a urine test in the mailbox. We will be the ones delivering the service, getting to the 70 per cent, getting the data into the medical record, building prevention.”

He says conversations with the NHS are open, and will probably start in earnest in the third quarter of 2019, including with Boots. Like Yonatan, the company’s chief commercial officer, and UK and Europe managing director, Katherine Ward, has a public service background, and was recruited with 26 years’ experience of public and private health sectors in the UK. “This was designed for a $6 reimbursement scheme in the US. This is not a $50 box,” he says.

As for the rest of pharmacy, Yonatan says: “We’re a white label company. Usually the box doesn’t say Dip UTI. We don’t want to spend energy (or money) getting the patient to trust a brand. This can say Boots, or another pharmacy, or it can say NHS. If a pharmacy group wants this to be branded because patients trust the brand, or if to sell on Amazon it needs to say ‘Amazon Healthcare Now’ we’ll play along; the patient matters most.”

The product

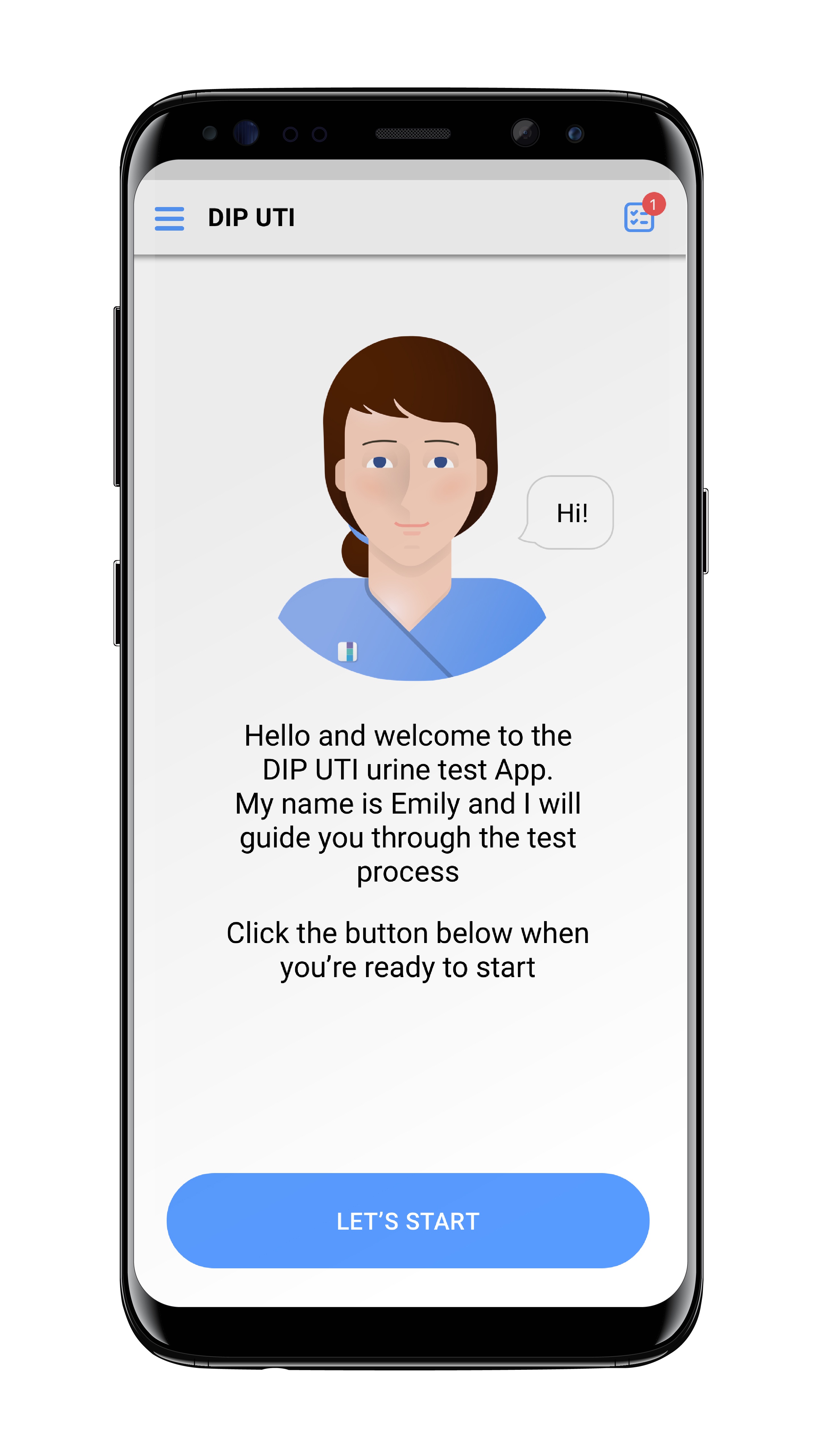

The DIP UTI test kit combines a traditional dipstick test, a no-mess pop-up cup to collect a urine sample, and an app with the latest scanning technology that is clinically comparable to a laboratory digital analyzer and a virtual nurse to talk users through the test.

The DIP UTI test kit is already being used within the NHS to monitor diabetes and kidney transplant patients. It has been adopted by the NHS Innovation Accelerator scheme, which fast-tracks evidence-based technologies with the potential to deliver major improvements in patient care.

In the ongoing trial in Boots pharmacies in London, Sheffield and Cardiff, pharmacists can offer the test kit to women who suspect they have a urinary tract infection, and provide a course of antibiotics if the results are indicative of a UTI. Once patients have downloaded the DIP UTI app, a virtual nurse called Emily talks them through the test and helps them avoid common pitfalls associated with urine-analysis dipsticks, which traditionally rely on trained staff comparing the colour block on a guide with that on the reagent strip.

In the ongoing trial in Boots pharmacies in London, Sheffield and Cardiff, pharmacists can offer the test kit to women who suspect they have a urinary tract infection, and provide a course of antibiotics if the results are indicative of a UTI. Once patients have downloaded the DIP UTI app, a virtual nurse called Emily talks them through the test and helps them avoid common pitfalls associated with urine-analysis dipsticks, which traditionally rely on trained staff comparing the colour block on a guide with that on the reagent strip.

The DIP UTI test kit provides a far more accurate interpretation of any changes and is as accurate as a digital analyzer. The dipstick is placed on a colour-board and then scanned by the smartphone app, which references colour blocks on the board to colour correct a scanned image of the dipstick and eliminate any variations due to different phones and lighting conditions.

Further screening kits and apps are in development.