Focus on value, not just on savings

In Running Your Business

Follow this topic

Bookmark

Record learning outcomes

Using lessons learned while advising the UK Government in its most recent negotiations with the pharmaceutical industry, health economist Leela Barham casts her eye over the Company Chemists’ Association’s claims that spending more on community pharmacy could save the NHS in England £1.9 billion a year.

The spending review is big-ticket policy: it’s the opportunity for anyone and everyone to put their case for public funding to Her Majesty’s Treasury (HMT). Community pharmacy in England is no different.

In its representations, the Company Chemists’ Association (CCA) focused on a case for investing in community pharmacy and estimated the benefits of doing so.1 As the sector starts negotiations on the successor to the Community Pharmacy Contractual Framework (CPCF) 2019-2024, there’s much at stake. Anticipating the perspective of the officials can help to shore up the case.

The CCA compiled a range of evidence, citing six references with a focus on the costs and benefits of doing more in community pharmacy, from hypertension screening to emergency hormonal contraception (EHC), Public Health England’s work from 2014 on tackling high blood pressure, the International Longevity Centre’s 2018 work on flu vaccination and PricewaterhouseCoopers’ 2016 report on the value of community pharmacy.

Unfortunately, this evidence now looks a little dated and, of course, it all pre-dates the pandemic. Civil servants are likely to ask, what’s out there now? That should be on the sector’s ‘to do’ list – not only to leverage any new evidence on the value of community pharmacy that is available, but also to find the gaps. There may still be time to fill them.

Matching the cash and the payoff

The Treasury (HMT) asks for representations to focus on the likely effectiveness, the deliverability and the value for money of proposals, the costs of benefits, as well as the priorities set out by the Government for the review.

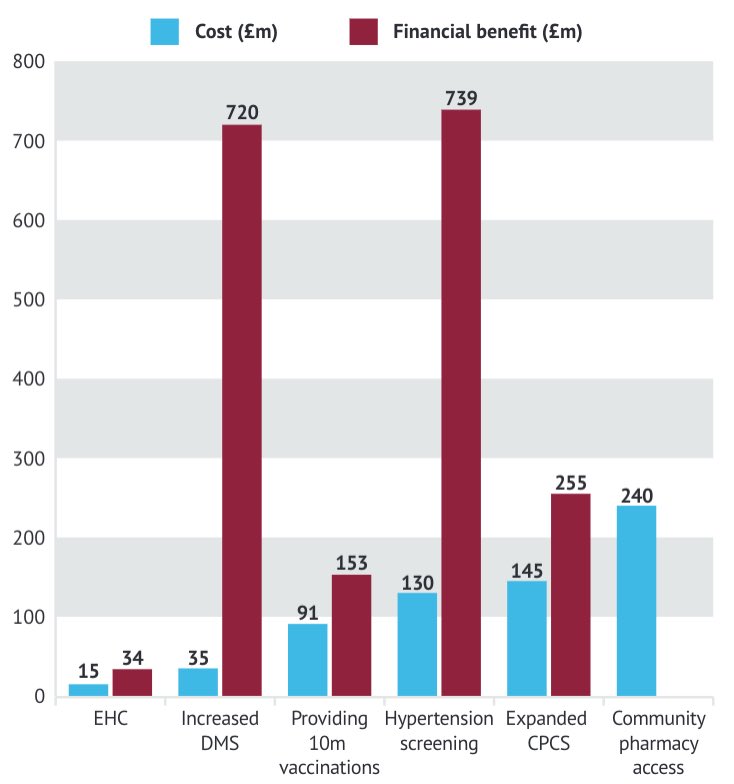

The CCA’s contribution does just this. Chart 1 (right) illustrates the numbers the CCA put forward for both the costs and the financial benefits of expanding a range of clinical activities in community pharmacies across England, ordered from the lowest funding ask to the highest.

The CCA’s contribution does just this. Chart 1 (right) illustrates the numbers the CCA put forward for both the costs and the financial benefits of expanding a range of clinical activities in community pharmacies across England, ordered from the lowest funding ask to the highest.

The numbers on the whole look good; there’s a payoff for them all – with one exception. There is no estimate for the financial benefit of community pharmacy access, which is unfortunate as it’s the biggest ask at £240 million. It’s an understandable gap; measuring the value of community pharmacy in a meaningful way is no mean feat. But a gap like that will attract the eyes of HMT’s civil servants.

Economists in HMT, across other Government departments and in arm’s length bodies, will be asked for their view of the evidence and, in particular, calculations for costs and benefits. The evidence base and the CCA calculations fall in the category of ‘pragmatic best efforts’. Extrapolation from existing work is often useful in providing a starting estimate, but equally there will be some assumptions that drive results.

For example, the CCA draws on analysis from the International Longevity Centre (ILC)’s 2018 work (funded by Sequirus, a flu vaccine manufacturer)2 to help with the estimated payoff from more vaccinations being delivered in community pharmacy. The original work illustrates the importance of key assumptions – not least the effectiveness of vaccination and the coverage – but also how uncertain the payoff can be. In two of three scenarios modelled by the Centre, flu vaccination cost more than the financial benefits it generated (meaning it had a cost:benefit ratio of less than one).

The CCA estimates have been recalculated in Table 1 to provide the cost:benefit ratios. If you can’t afford it all, it makes sense to focus investment on the activities with the best return first, then invest in the next best deal, and so on. On that basis, increasing activity in the Discharge Medicine Service (DMS) looks a strong contender for investment. But it’s far from clear that there will always be a payoff in real life, as the ILC work illustrates. Unfortunately, scepticism on the part of civil servants is a given.

| Table 1: Cost:benefit ratios for increased clinical activity in community pharmacy (CCA estimates) | |||

| Cost (£m) | Financial benefit (£) | Cost:benefit ratio | |

| Increased Discharge Medicines Service (DMS) | 35 | 720 | 20.6 |

| Hypertension screening | 130 | 739 | 5.7 |

| Emergency hormonal contraception (EHC) | 15 | 34 | 2.3 |

| Expanded Community Pharmacist Consultation Service (CPCS) | 145 | 255 | 1.8 |

| Providing 10 million vaccinations | 91 | 153 | 1.7 |

| Community pharmacy access | 240 | ||

| TOTAL | 656 | 1,901 | |

Shoring up any estimates is wise, and triangulation can be useful. For example, the CCA suggests that a nationally commissioned EHC service in community pharmacy could result in up to 500,000 consultations.

That looks like an overestimate. The most recent Office for National Statistics (ONS) data says that 712,680 births were recorded in 2019,3 while Public Health England data suggests that one third of births are unplanned or ambivalent (so around 235,000 or so).4 The most recent NHS Digital data puts the number of prescriptions for emergency contraception at 44,400 in Sexual and Reproductive Health Services in 2020/21 and 90,000 dispensed in the community in 2020. NHS Digital data also reveals a dramatic – over 64 per cent – drop in demand for emergency contraception services in 2020 versus 2010.5

It’s not just the money

Money matters, so it’s tempting to focus on the pounds and pence. The CCA doesn’t fall into that trap (although perhaps our reporting did6). It uses money as just one metric, highlighting the potential to increase NHS capacity, improve population health and patient outcomes, and target health inequalities – the last being a renewed policy drive of the current government.

It might also be tempting to focus on doing more purely from an activity basis. Quality matters and value can be added beyond the income stream. Going back to that EHC example, increasing access through an NHS-funded service delivered in a community pharmacy could offer convenience that is highly valued by women. Even if that isn’t quantified, it should still be a consideration. This is, however, pure speculation; the best way to explore the full value of offering more EHC in community pharmacy is by seeking the views of women. This would have the added benefit of helping with calculations to calibrate assumptions: how will women’s behaviour change and can that be used to generate more realistic estimates of how much activity could take place in community pharmacy?

There is also a more fundamental question: should the ‘fee for service’ funding model and way of thinking be so dominant? Is there a hybrid of per capita and fee for service that makes sense, and that could help align the value community pharmacy can offer to patients and the NHS beyond a transactional approach?

The spending review ended on 27 October, but community pharmacy will need to keep working on its value as it readies for negotiations on the next CPCF. The CCA spending review submission provides a strong starting point, but there is still much to do.