Branded generic prescribing: Which LPC regions are most affected?

In News

Follow this topic

Bookmark

Record learning outcomes

P3pharmacy hears why it is still an uphill battle to get some commissioners to move away from branded generics

England’s 42 integrated care boards (ICBs) appear to be facing eye-watering deficits, with a survey of 23 ICBs by campaigning publication The Lowdown finding that 18 were overspent by the end of the 2023/24 financial year – and most anticipating a worse set of figures once the current financial year has wrapped up.

ICB chiefs will have been given orders to trim costs wherever they can, and like their Clinical Commissioning Group (CCG) predecessors they are all too often tempted by the immediate savings that branded generic medicines appear to offer.

These drugs, which are identical to generic alternatives in chemical terms, are sold by manufacturers at prices that includes the cost of their marketing efforts but are often lower than those for generic equivalents because the products don’t contribute to the purchase profit levels set within the Community Pharmacy Contractual Framework.

“Pharmacies must buy them at full price but are reimbursed by the government at the same rate, minus a five per cent clawback as per the English Drug Tariff. This means pharmacies lose money on every branded generic they dispense, harming their financial viability.”

PharmData says its analysis suggests that pharmacies lose an average of 89p for every branded generic they dispense, explaining: “This is based on the missed potential profit margin from a generic product being prescribed and dispensed, and the government clawback of five per cent for each branded generic dispensed.”

It’s an old problem – the Community Pharmacy England (CPE) topic page on branded generics still makes reference to CCGs rather than ICBs – but in at least some parts of the country progress appears to be frustratingly slow.

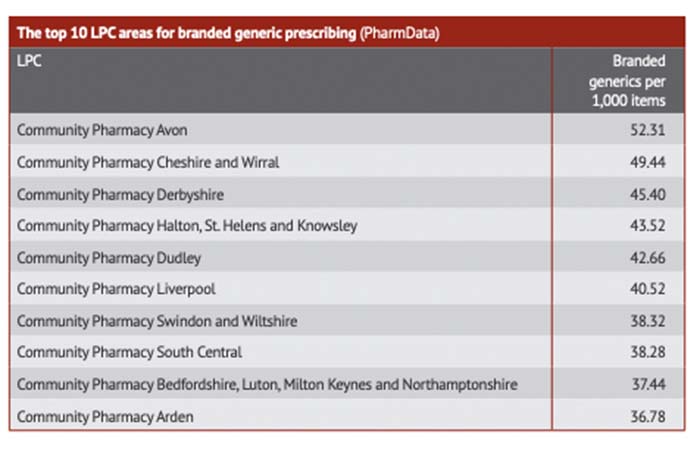

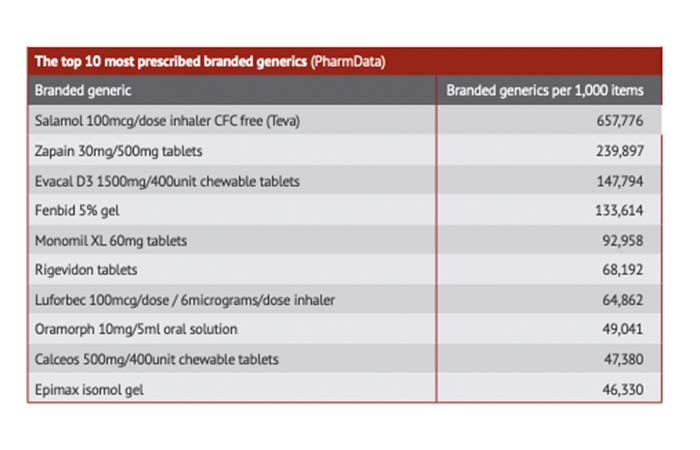

PharmData has found that in 2023 a total of 33,977,424 branded generic items were dispensed, leading to a combined loss of £30.2m to contractors. It also says that data for October 2024 shows that Teva’s Salamol 100mcg inhaler is far and away the most dispensed product by monthly volume at 657,776 items, more than double the second most dispensed (Zapain 30mg/500mg tablets at 239,897 items).

The findings suggest that if the 89p figure is correct, these two products alone lost pharmacies £798,928 in a single month, with the top 10 products losing contractors £1.38m collectively.

Core funding undermined

“Branded generic prescribing is often encouraged at local level because it appears to offer commissioners cost saving opportunities,” says Community Pharmacy England’s funding strategy manager Jack Cresswell.

“However, this practice is detrimental to pharmacy owners who receive these prescriptions, as it undermines the intended mechanism of delivering their core funding. Reimbursement prices for generic medicines are intentionally set in in the Drug Tariff in order to deliver retained margin to the dispensing contractor.”

And it may not even save ICBs money in the long run: “The reduction in prices at local level may also lead to increased costs for the NHS as a whole, since at the national level adjustments must be made to ensure full delivery of the agreed pharmacy funding settlement.

“Generic prescribing has well recognised long-term economic benefits for the NHS. When products are prescribed generically, pharmacies seek to obtain the best available generics prices, driving down the prices being charged by wholesalers and manufacturers and in turn the Drug Tariff reimbursement prices and costs for the NHS.

“Prescribing branded generics or off - patent branded medicines profoundly affects the competition that drives down prices in the generics market and acts to drive up costs to the NHS.

“Aside from the financial implications for pharmacies and the NHS, branded generic prescribing can also lead to supply issues for patients.”

Persuasive efforts

LPC chiefs have been banging on doors to persuade their local commissioners that something needs to change. “This is a massive issue nationally,” Community Pharmacy North East London chief executive Shilpa Shah tells P3pharmacy. “It’s really detrimental to community pharmacy.”

Speaking at the 2023 Pharmacy Show alongside ICB chief pharmacist Raliat Onatade, Shah said close collaboration between the two organisations had led to work on a position statement outlining that it is not appropriate to use branded generics as a cost-saving tool.

At the time, Onatade praised Shah’s efforts in “quietly and persistently” raising the issue, saying that commissioners are being “pushed to make millions and millions of pounds in savings in the drugs budget,” but had been forced to reckon with “why we in the ICB are doing something that has such a negative impact on community pharmacies”.

A year later, Shah tells us the work is “not quite finalised” but that her team and the ICB are “working towards an agreement” with the topic discussed at monthly meetings.

Fiona Lowe, chief executive of Community Pharmacy Arden – which features in the top 10 most affected LPCs – and Community Pharmacy Herefordshire and Worcestershire, says it has “always been a bit of a battle around branded generics”.

There are some positive signs, she tells P3pharmacy, with commissioners in Herefordshire and Worcestershire having come to the conclusion that prescribing these products “is not, in the long term, a cost-effective way of doing it – so they largely don’t”.

She says they have “largely abandoned trying to do any new branded generics” and only have “very few” remaining that are routinely used.

However, Coventry is a different story. “We always used to have shedloads of them – it was constant,” she says.

The ICB medicines optimisation team “has a big number it has got to hit” in terms of savings and that “it’s very tempting on a short-term basis to do it, so they have been a bit more difficult [but] we have had conversations and they are getting a little bit more realistic”.

As part of the Midlands Medicines Optimisation Group, Lowe has helped develop a similar position statement to Shah’s, in which the group argues that these medicines should not be used “unless there is a clinical reason to do so”.

The group looks at a range of issues including shortages, with branded generics comprising “one piece of the jigsaw,” she believes. “I think I’m the only LPC person on the group, the others are all chief pharmacists or work in medicines optimisation. That probably carries a bit more weight.”

A three-page statement was circulated to ICBs in the summer “and that’s pretty much where we’re at,” she says, adding that it is “too early to say” what impact it may have had.

Lowe hopes commissioners realise that there are “an awful lot of wooden dollar amounts rather than actual savings” but worries they “might turn a blind eye to that if it suits them to hit their immediate targets”.